Articolo tratto da THE ECONOMIST Dec 26th 1992-Jan 8th 1993

“A World History”, by Dwight Bogdanov and Vladimir Lowell (University of California in Moscow, 640 pages or 27 sight-bites, published 2992), has one of the best accounts of democracy’s post-1991 failure. He is its Chapter 13.

This was an opportunity of a magnitude the world had rarely seen before. As Chapter 12 explained, the three-sided War of Ideas that had occupied most of the 20th century ended in a sweeping victory for the once apparently doomed forces of liberalism. The defeat of racial totalitarianism in 1945 having been followed by the defeat of communist totalitarianism in 1989-91, the victorious pluralists seemed to have the future at their feet.

The collapse of communism brought universal agreement that there was no serious alternative to free-market capitalism as the way to organise economic life. It was almost as widely agreed that multi-party democracy was the best form of politics; only a handful of authoritarians anxious to preserve their own power – most of them in Muslim south-west Asia – and the old men still running China openly stood aside from the new orthodoxy. To this ideological triumph was added, in the Gulf war of 1991, a military success that appeared to confirm the new balance of power. The pluralist alliance possessed a technological advantage in the weapons of war that could, it seemed, defeat almost any possible adversary.

All this was potentially a greater change in the course of history than Britain’s defeat of Napoleonic France in 1815. That decided who was to be militarily dominant in the 19th century, but it did not put an end to the ideological fallacy that had begun in France in 1789 and reappeared in new shape in Russia in 1917. The events of 1989-91 could also have proved more decisive than the victory of the Reformation in the 17th centuty. That changed the ideological scene, but it did nothing to decide the military and potical balance of power in Europe.

Perhaps not since the battle of Actium in 31BC, which made possible the Pax Romana of the next two centuries, had there been such a chance to remake the world; and in AD1991, unlike 31BC, the central idea on which the remaking would have been based was the victors’ belief in every man’s right to political and economic freedom.

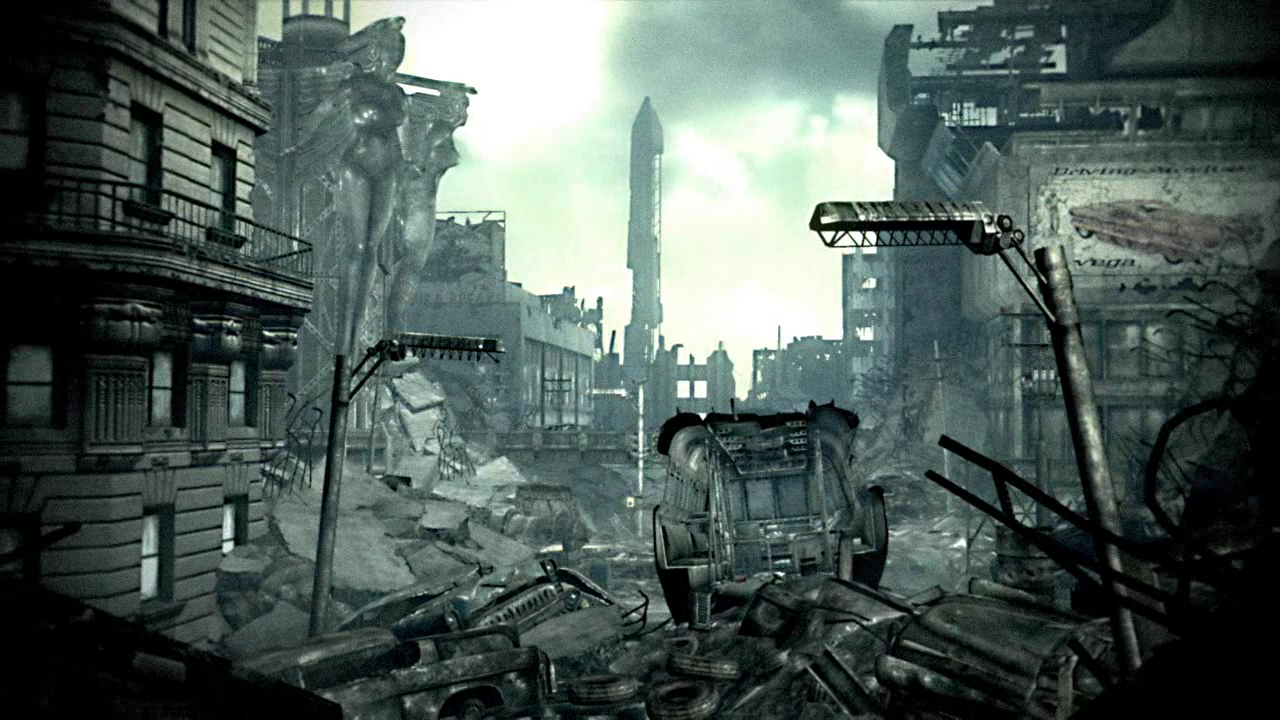

The remaking never happened, for reasons that modern students of history can understand better than the people of the time did. The 21st century became the “century of disasters”, and it was not until the 2300s that it began to be possible to reassemble the beginnings of today’s General Confederation of Democracies. The post-1991 failure happened because ofa failure of clear thinking, failure of imagination, and a failure of will.

Pillar by pillar, it fell

The failure of clear thinking applied to all three members of the victorious coalition – the United States, the European. Community and Japan. They could, if they wished, have brought a share of liberty and prosperity to much of the rest of the world by the end of the 21st century. They did wish it. But they failed to see that to succeed they had to remain a partnership. Instead, each of the three almost at once started to assert itself against the others. By 2006, the year of the last American military withdrawal from Europe and Asia, the coalition had collapsed.

At first this was blamed on economic rivalty. There were indeed, even before 1991, sharp animosities in American-European-Japanese trading relations. These grew still sharper in the 1990s. After a briefglow of optimism, the attempt to draw up a more liberal set of trading rules had to be abandoned as protection led to retaliation, which produced counter-retaliation, and so on. By the end of the century there was virtually no rule book at all. The disruption of trade hurt the rich of the world; but it hurt the poor even more, because in the trade war that followed they were defenceless.

Beneath the economic rivalry, however, it can now be seen that a deeper cause of division was at work. It had become common in the late 20th century for the “advanced” countries to claim that they, at least, had overcome the disease called nationalism. They exaggerated their cure. Worse, the force that had given birth to nationalism in the 18th and 19th centuries had now moved on to a larger stage. The desire to create a sense of identity by marking oneself off from others – by separating “us” from “them” – had spread from single countries to whole regions. No shared political or philosophicai belief was strong enough to resist it. Hyper-nationalism had appeared. The hoped-for new world order broke up into the European Restoration, the China-Japan Co-operation Sphere, and the New Americanism.

The failure of imagination that made this worse was specifically Europe’s.The Europeans, seeking to recapture some of the power they had lost in the world wars of the first half of the 20th century, had long been trying to set up a European union. The sudden defeat of communism made them think it was necessary to accelerate the process. In doing so, they concentrated on the western end of Europe, where the idea had started – and failed to picture the consequences of excluding the eastern, communist part of the continent.

The West Europeans shut their doors to many of Eastern Europe’s exports, thereby condemning countries like Poland, Hungary and Bohemia – which with help might have managed the leap to democratic capitalism – to a long period of economic and political disorder. The West Europeans also failed to halt the slaughter that accompanied the break-up of Yugoslavia. The subsequent horrors in the ex-Soviet Union were perhaps too huge for anyone to halt; but estern Europe could at least have built a barrier, from the Baltic to the Black Sea, between itself and the chaos in Russia.

As it was, the West Europeans spent the 1990s quarrelling over rival constitutions; the anarchy in the east spread to the border of Germany; and by 2008 free Europe was a barely bigger place than it had been in 1988.

The failure of will was America’s. 1992 the United States was the only power that might have prevented all this. It had military strength, a still-large economy, and an ability to see the world as a whole. The optimists believed that the exhilaration of the 20th century, when the United States had twice saved the world for democracy, would rescue Americans from a return to the isolationism they had chosen for them-selves in the 19th century – and that America would once again be the saviour.

The optimists were wrong. America’s economic and racial troubles, and the growing acrimony of its relations with Europe and Japan, had eaten away its will to lead. President Clinton kept the attempt for a time, but by the end of the century introversion had won. The Buchanan Doctrine of 2003 – enunciated to Congress 180 years to the day after President Monroe’s earlier declaration of the self-sufficiency of the Americas – made America’s 21st century a new version of its 19th century. The 20th had been only a marvellous aberration.

Since the United States was now gentler in its treatment of other Americans, the new version was better than the old. The United States itself took a few decades to get used to its narrower horizons, and to sort out its internal problems. But by the mid-2000s the western hemisphere as a whole was tranquil, fairly prosperous and almost wholly democratic – an undogmatic association of fee-trading nations protected by its encircling oceans (and the nuclear armoury of the United States) from the turmoil elsewhere. Even Quebec eventually joined the Pan-American Free Trade Area, on condition its name be spelt with an accent aigu.

This relatively contented western hemisphere was, alas, no model for the rest of the world. There, the consequences of the disintegration of the pluralist alliance began to work themselves out, one by one.

It was no longer possible to hope, as many had hoped at the start of the 1990s, that the democracies might sometimes send their soldiers to save people from the terrible events of that time – in some countries mass starvation and its accompanying banditry, in others a brutal suppression of democracy by military dictators, elsewhere the collapse of all organised government. The Joint Interim Regime in Somalia (1993-98) showed what could be done. It distributed the food that saved several million people from death, rebuilt the country’s infrastructure, and administered the place until the election of governments for the two countries into which the Somalis decided to divide themselves. But the Somalia intervention was the last of its kind.

Intervention cost money, and lives. If this was hard for the democracies to accept when they were still allies who shared the burden, it became impossible when they had broken up. The idea that the rest of the world might be helped along the road to freedom and prosperity faded from people’s thoughts. After the failure in Yugoslavia, Western Europe began to lower a mental curtain between itself and events east of Vienna. The guiding lamp of democracy grew dim. Dictators everywhere took new heart; the doctrine that sovereignty permitted any abuse of human rights – cuius regio, eius potestas – took new root.

The retreat from democratic hopes was made more rapid by the impoverishment that followed the tearing-up of odd trade rules. Many African and Asian countries, suddenly even poorer than before, were easy prey for dictatorial seizures of power. By 2030 a larger proportion of the world’s population was living under authoritarian rule than half a century earlier.

The new giants

Out of this confusion arose two new great powers, which between them came to dominate the 22nd and 23rd centuries. The first – predictably, though not many people realised in time where the statistics were painting – was China.

The Chinese economy could not quite keep up the 9% real annual growth rate it had reached in the 1980s; that period, the opening up of agriculture and small industry, was the easy one. But even when it faced the more difficult task of buildng a modern mass-production industry on the market system, China continued to grow faster than any other big country, sometimes by a margin of two or three percentage points a year. Since it had over a billion people, that made it a great economic power by the 2020s; and, since it already possessed nuclear weapons, and was now able to pay for formidable non-nuclear armed forces as well it became a great political power too.

It was not, however, to become a democracy. It ceased to be a communist society, of course, when its ruling party gave up control of the economy. But that ruling party continued to declare, even when it no longer called itself Communist, that a country as big and disparate as China needed a strong central government, especially if it was to have a vigorous foreign policy. As examples, the ex-Communists pointed both to China’s own history and, closer in time to the de facto one-party system devised by post-1945 Japan. They struck a deal with their former Nationalist enemies, when unification with Taiwan took place in 2007, and reunified China settled down to be a market economy under an authoritarian political leadership. It was by no means the first time the world had seen that combination.

This China’s first big foreign-policy challenge was what to do with Japan. Many Japanese, seeing the way things were going in China, were by the end of the 1990s arguing that if Japan wanted to keep its independence it must become a nuclear power. But memories of the atomic bombing of two Japanese towns in 1945, and the fact that most of Japan’s people lived in a handful of vulnerable coastal cities, produced strong opposition to this idea within Japan itself: and, in 2009, China delivered its veto.

The detonation of a Chinese nuclear warhead over the sea off Yokohama caused no casualties, except for the unlucky crew of a tanker that had ignored the warnings. It was the last martial use of nuclear power. But it changed the map of eastern Asia, and from then on Japan was to China what Switzerland had earlier been to its big European neighbours: a rich, efficient provider of specialised financial and business products, independent in its domestic affairs, but small and unassertive enough (Japan’s population was now less than a tenth of China’s, and ageing fast) to be any kind of rival on the international scene.

Now China had to decide what its relations should be with the other new great power of the 21st century. This was the force that burst upon the world, almost as explosively as a similar phenomenon had done 1,400 years earlier, out of the long-sluggish Muslim world: the New Caliphate, as amused outsiders called it until they learnt not to joke.

The failure of Muslims to match the political and economic advance of the democracies had puzzled the 19th and 20th centuries. These people had, after all, an earlier history of dazzling achievement; more recently many of them had shown great skill in science and the arts; and, since the early 20th century, their lands had contained most ofthe industrial world’s chief source of energy. All they lacked, it seemed, was the right combination of circumstances for organising themselves into a coherent power. That this analysis was correct was demonstrated by the results of Colonel Algosaibi’s. coup in Saudi Arabia in 2011.

Algosaibi succeeded, where so many would-be unifiers of Islam had failed, because he quickly took control of almost all the Gulf’s oil; because he could point Muslims towards a new geopolitical target; and, above all, because by 2011 Muslims felt that at last they had a chance to work off their ancient resentment against the now-splintered western world.

The revolutionaries in ex-Saudi Arabia, now the Islamic Republic of Arabia, offered to share the Gulf’s oil wealth with other Muslims in return for a foreign-policy alliance and a joint army. Most of eastern Islam stayed aloof, but almost all the Arabs joined the movement; Iran found it expedient to compromise; and even Pakistan made a contribution to the army. The driving force was not religion, though that created the movement’s sense of identity. It was hyper-nationalism, another region’s demand to stride upon the stage.

The first victim was Turkey, a country accused of betraying its fellow Muslims in pursuit of the false western idea of democracy. A bungled British-French expedition to Antioch (2014) failed to prevent the invasion of Turkey. The forces of the New Caliphate swept up to the Bosporus and, in the War of the Sanjak (2016), established their first bridgehead in south-eastern Europe.

The main target, however, was the decaying corpse of Russia, itself a fragment of the broken Soviet Union; and here the New Caliphate found the basis for the alliance with China that was to shape the next two centuries. The Chinese wanted to recover the Siberian tenitories they had lost to Russia in the “unequal treaties” of the 19th century. The new Muslim power started by wanting to remove the last Russian influence from the Muslim southern parts of the ex-Soviet Union; and then, having achieved that, found itself pushing still farther north. China supplied most of the weapons the Caliphate needed. The Caliphate provided China with a secure western flank.

By the mid-21st century, all this had been accomplished, because there was nobody to forbid it. The Americans politely repeated that the rest ofthe world was no business of theirs. The West Europeans, divided, isolated from America, and shocked by the Antioch disaster, did not intervene. India, intimidated by the new Muslim power and weakened by the secession of some of its north-western states, was helpless. Africa south of the Sahara had for the moment vanished out of history.

The Russians, after years of economic disorder and short-lived governments, were in no position to resist. Their army was demoralised, and they did not use their decrepit nuclear weapons for fear of an over-whelming Chinese response. In two brief campaigns Russia’s borders were pushed back to the Urals and to an uneasy line running from the central Urals to the Sea of Azov. The exodus of refugees added to the pressures on Western Europe. The Chinese-Muslim alliance, knowing the Europeans still had a powerful nuclear force, cautiously decided to push its expansion no further; but it had become the new superpower.

The end of the cycle

Looking back from 2992, one can see why the democracies missed the great opportunity they were given in the 1990s. The fact that they had had to spend the 20th century fighting their two-front War of Ideas, against communism and fascism, was itself a sign that a cycle of history was approaching its end. The democracies needed to re-examine the ideas that had created this cycle; but they left the re-examination too late.

These democracies were the product of a period that had begun 500 years earlier, in the pair of events known as the Renaissance and the Reformation. That was when the rights and responsibilities of the individual began to be asserted against the spirit of authority that had dominated the previous era. It was also when the power of rationality reasserted itself after an Age of Faith. Both of these were necessary changes, and between them they produced the European-American culture that shaped the next half-millennium. But, as usual, the changes that corrected past errors went too far, and became new errors.

By the 18th century it was being argued that man had now reached an Age of Reason, in which human beings could understand and master every aspect of their lives. This proved false. It led, among other things, to the French revolution of 1789 and the Russian revolution of 1917, both of which claimed to speak for human rights but in fact crushed them, and both of which did irrational things in the name of reason. The fascist upheaval of the 1920s and 1930s was in part a reaction to this, a violent return to the idea that blood and feeling were the true guides to human action. Nationalism, and its son hyper-nationalism, were milder versions of the same reaction.

It was time for a readjustment. A new balance was needed between the analytic part of the human mind and the instinctive part, between rationality and feeling; only then could man address the world more steadily. And a new bargain had to be struck between the claims of individual freedom and the claims of a universal morality; only then could law and liberty swing evenly on the scales. Because they did not tackle these problems in time, the democracies marched straight from the climax of their 20th-century victory into anti-climax. They did not know what to do next.

It is easy in 2992 to say this. Today’s 3 billion people have managed, at least in part, to do those rebalancings. And they have seen China and the Muslims move into their own new period of division and uncertainty; Russia reassemble itself; America come back into the world; and Europe settle for prosy but workable reality. The conditions of a Pax Democratica have at last arrived. If only the people of 1992 had seen what their distant descendants could do.